Tracer transport

Transport operator

To model marine biogeochemical tracers on a global scale we need to be able to account for their movement within the 3D ocean. We do this with tracer transport operators, generically denoted by $\mathcal{T}$. These operators act on a tracer field to give its divergence. In other words, take a tracer with concentration $x(\boldsymbol{r})$ at location $\boldsymbol{r}$ that is transported by some mechanism represented by the operator $\mathcal{T}$. Its divergence at $\boldsymbol{r}$ is then $(\mathcal{T} x)(\boldsymbol{r})$.

In the case of the ocean circulation, i.e., the currents and eddies that transport marine tracers floating around in sea water, the transport operator can be represented by

\[\mathcal{T} = \nabla \cdot \left[ \boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{r}) - \mathbf{K}(\boldsymbol{r}) \nabla \right]\]

The $\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{r})$ term represents the mean marine current velocity at location $\boldsymbol{r}$. Thus, $\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{r})$ is a 3D vector aligned with the ocean currents and whose amplitude, in m/s, gives the velocity of the moving sea water. The $\mathbf{K}(\boldsymbol{r})$ term is a 3×3 matrix that represents eddy diffusivity. That is, it reproduces the effective mixing effect of unresolved eddies, the turbulent vortices that are too small relative to the model grid to be explicitly captured. In earlier models of the ocean circulation, like OCIM's ancestor (denoted OCIM0 in AIBECS), $\mathbf{K}$ was diagonal. Since OCIM1, $\mathbf{K}$ contains non-diagonal to orient mixing preferentially along isopycnals.

In the case of sinking particles, one can assume that they are only transported downwards with some terminal settling velocity $\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{r}).$ The corresponding transport operator is then simply

\[\mathcal{T} = \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{r}).\]

Discretization

In order to represent a marine tracer on a computer one needs to discretize the 3D ocean into a discrete grid, i.e., a grid with a finite number of boxes. One can go a long way towards understanding what a tracer transport operator is by playing with a simple model with only a few boxes, which is the goal of this piece of documentation.

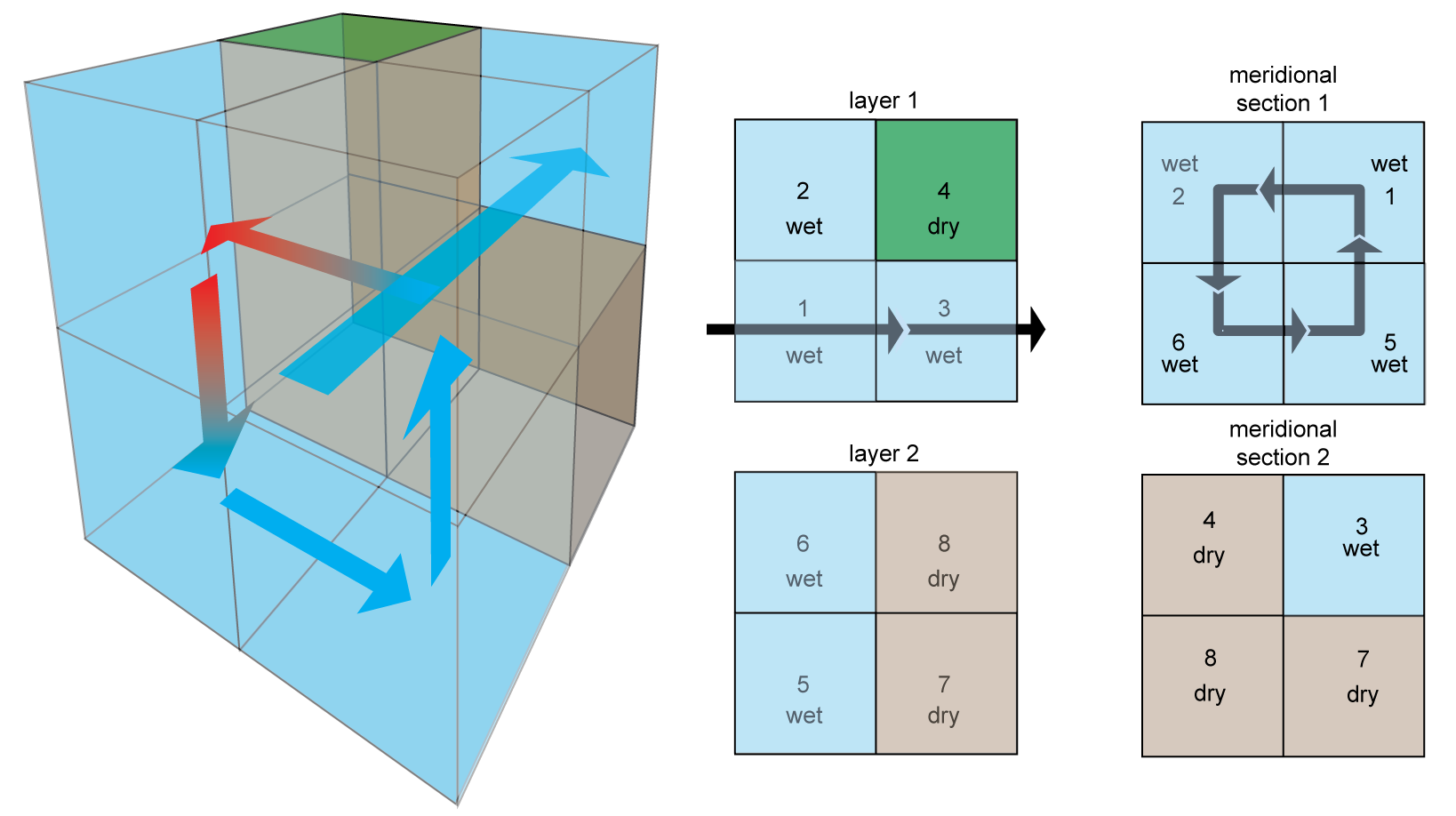

The simple box model we consider is embedded in a 2×2×2 "shoebox". It has 5 wet boxes and 3 dry boxes, as illustrated below:

An example of discretized advection, $\boldsymbol{u}$, is shown on the image above, and consists of

- a meridional overturning circulation flowing in a cycle through boxes 1 → 2 → 6 → 5 → 1 (shown in the meridional section 1 panel)

- a zonal current in a reentrant cycling through boxes 1 → 3 → 1 (shown in the layer 1 panel)

This circulation is available as the Primeau_2x2x2 model. You can load it in AIBECS via

grd, T = Primeau_2x2x2.load()Note that this circulation also contains vertical mixing representing deep convection between boxes 2 ↔ 6 (not shown on the image)

Vectorization

In AIBECS, tracers are represented by column vectors. That is, the 3D tracer field, $x(\boldsymbol{r})$, is vectorized, in the sense that the concentrations in each box are rearranged into a column vector.

The continuous transport operator $\mathcal{T}$ can then be represented by a matrix, denoted by $\mathbf{T}$, and sometimes called the transport matrix. It turns out that in most cases, this matrix is sparse.

A sparse matrix behaves the same way as a regular matrix. The only difference is that in a sparse matrix the majority of the entries are zeros. These zeros are not stored explicitly to save computer memory making it possible to deal with fairly high resolution ocean models.

Mathematically, the discretization and vectorization convert an expression with partial derivatives into a matrix vector product. In summary, for the ocean circulation, we do the following conversion

\[(\mathcal{T} x)(\boldsymbol{r}) = \nabla \cdot \left[ \boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{r}) - \mathbf{K}(\boldsymbol{r}) \nabla \right] x(\boldsymbol{r}) \longrightarrow \mathbf{T} \, \boldsymbol{x}\]

Ocean circulations in AIBECS

In AIBECS, there are currently a few available circulations that you can directly load with the AIBECS:

Primeau_2x2x2, the circulation described in this documentation pageTwoBoxModel, the 2-box model of the Sarmiento and Gruber (2006) bookArcher_etal_2000, the 3-box model of Archer et al. (2000) (also used in the Sarmiento and Gruber (2006) book)OCIM0, the unnamed precursor of the OCIM1 (and which should actually be named OCIM0.1)OCIM1OCIM2

To load any of these, you just need to do

grd, T = Circulation.load()where Circulation is one of the circulations listed above.

If you are adventurous, you can create your own circulations. AIBECS provides some tools for this. (This is how the Primeau_2x2x2 and Archer_etal_2000 circulations were created.)

Sinking particles in AIBECS

There are no loadable transport operators for sinking particles, because there are too many ways to represent sinking particles. However, the AIBECS provides tools to create your own transport operators by providing a scalar or a vector of the downward settling velocities, w. For example, you can create the transport operator for particles sinking at 100 m/d everywhere simply via

T = transportoperator(grd, w=100u"m/d")